<The Journal of Theological Studies>(옥스퍼드대학 출판사)에 소개된 위트니스 리의 삼위일체론

-

관리자

관리자 - 2269

- 2

The Journal of Theological Studies, 2025, XX, 1–32

The Journal of Theological Studies, 2025, XX, 1–32

https://academic.oup.com/jts/article/76/1/238/8046240

Advance access publication 28 February 2025

Article

Essence and Economy: An Introduction to

Witness Lee’s Doctrine of the Trinity

Michael M. C.Reardon1, and Brian Siu KitChiu2,

1Canada Christian College, Whitby, Ontario, Canada

2Talbot School of Theology, Biola University, La Mirada, CA, USA

mreardon@canadachristiancollege.com

한글 번역 - 본질과 경륜: 위트니스 리의 삼위일체 교리에 대한 소개

ABSTRACT

Witness Lee (1905–97), a prominent figure among Chinese and Chinese-American Christians, exerts a profound influence upon theological and ecclesiological currents in the Global South. He is less familiar to Western theologians—and in several instances, grossly misunderstood by them— due to a lack of peer-reviewed scholarship directly examining his corpus. This article addresses this lacuna in respect to Lee’s doctrine of the Trinity. We begin by discussing his overarching trinitarian framework, in relation to his portrayal both of the essential and economic aspects of the Trinity. We then turn to Lee’s doctrines of the eternal coexistence and coinherence of the divine hypostases in dialogue with both patristic and contemporary thinkers. Thereafter, we analyse Lee’s portrayal of the economic Trinity through six interrelated lenses that pervade his corpus: (1) the divine oikono-mia; (2) the ‘processed and consummated Triune God’; (3) the ‘compound Spirit’; (4) the ‘sev-enfold intensified Spirit’; (5) the ‘full ministry of Christ’; and (6) the Latin axiom opera Trinitatis ad extra indivisa sunt. We conclude by synthesizing Lee’s trinitarian commitments, discussing his unique contributions to modern trinitarian reflection, and offering a final assessment of how his intellectual topography squares with orthodox Nicene trinitarianism.

Witness Lee (1905–97), a prominent figure among Chinese and Chinese-American Christians, exerts a profound influence upon theological and ecclesiological currents in the Global South. He is less familiar to Western theologians, however, for three reasons: (1) his ministry emphasizes discipling lay Christians as opposed to directly engaging with academic scholarship; (2) perhaps relatedly, there is a paucity of scholarly engagement with his theology and influence; and (3) he has no oficial biography published in English.1 Notwithstanding this lack of awareness within the Western academy, Lee’s theology was strongly criticized by lay apol-ogists during the height of the countercult frenzy that swept the USA in the 1960s and 1970s.2

These apologists grossly misrepresented Lee’s teachings, particularly in relation to his doc-trine of the Trinity.3 In recent decades, some have disavowed their past evaluations of Lee. The Christian Research Institute (CRI), for example, a leading ‘anti-Lee’ voice under the direction of Walter Martin in the 1970s,4 conducted a six-year study of Lee’s teachings in the mid-2000s. The outcome of their study was a series of publications endorsing his theological orthodoxy including a special 2009 edition of the Christian Research Journal entitled ‘We Were Wrong: A Reassessment of the “Local Church” Movement’.5 Fuller Theological Seminary also examined Lee’s teachings, and published the findings of their 18-month investigation in 2006. Three of their conclusions are especially significant, in stating that Lee’s theology is (1) ‘unequivocally orthodox’; (2) represents ‘the genuine, historical, biblical Christian faith’; and (3) has ‘been grossly misrepresented and therefore most frequently misunderstood in the general Christian community, especially among those who classify themselves as evangelicals’.6

However, these statements aimed at evangelical audiences have not translated into mean-ingful research within the academy. Although Lee’s outsized impact on theology in the Global South has long been recognized—including in a two-page statement entered into the US Congressional Record in 2014—peer-reviewed research on it has only recently begun.7 Moreover, there is a bewildering dearth of investigations directly examining his corpus.8 This state of affairs has allowed half-century-old claims from countercult apologists to continue to circulate both digitally and in print.9 Religious scholar J. Gordon Melton commented upon this issue in response to one of the most pointed attacks against Lee—a now out-of-print volume by Neil Duddy entitled The God-Men:10

In light of the manner in which this book treated Lee, I can only suggest that The God-Men, and the other attacks upon the Local Church derived from it, be discarded, and that some other more capable and responsible Christian scholars set themselves the task of reviewing and examining Lee’s teachings.11

Melton went on to conclude, ‘[m]eanwhile I suggest, that we accept the confession of faith of the Local Church, a confession which is perfectly orthodox on essentials’. The present article takes up Melton’s charge to carefully examine Lee’s theology—at least in respect to his doctrine of the Trinity. We do so both through direct engagement with his writings and in dialogue with the ‘orthodox Nicene tradition’.12

1. METHODOLOGY AND AIMS

CRI’s 2009 report critiques previous investigations of Lee’s trinitarian theology: ‘in a different sense that same rebuke [concerning the understanding of “economy”] might well be addressed to those of us who missed a distinction frequently between the essential Trinity and the econom-ical Trinity’.13 This statement is especially germane to our present investigation. For Lee, the ‘most important truth’ for Christians to apprehend is ‘concerning the Triune God’,14 and the ‘most important, key words in the study of the Triune God’ are ‘essence and economy’.15 We thus follow Lee’s explicit approach in this article by utilizing an essential–economic framework to analyse his corpus.

Three questions about Lee’s trinitarianism have been raised by past researchers. (1) Does his outlook cohere with the orthodox Nicene tradition, or does it venture into modalistic or tritheistic territory? (2) Do his statements, especially those ones that have been misunderstood by countercult ministries, find support in the Nicene tradition—that is, in either patristic writ-ings and/or contemporary ones? (3) Does Lee’s articulation of the Trinity provide any insights, correctives, or contributions to modern trinitarian discourse?

To answer these questions, the article proceeds as follows. First, we survey Lee’s use of the essential/economic dichotomy and place it in dialogue with the Nicene tradition, broadly construed. Next, we examine Lee’s understanding of the doctrines of coexistence and coinher-ence—which form and inform his portrayal of the essential Trinity—in dialogue with patristic and contemporary thinkers.16 Thereafter, we analyse Lee’s portrayal of the economic Trinity through the lens of his concept of the divine oikonomia and five further interrelated concepts that pervade his corpus. Lastly, we synthesize Lee’s doctrinal commitments and discuss one of Lee’s potential contributions to modern trinitarian discourse—that is, that the study of the Divine Trinity would not be delimited only to intellectual apprehension, but would impact the subjective experience of believers and become a vehicle for believers to, in Lee’s terminology, experience, enjoy, and participate in the Triune God. But before doing so, we turn to a brief biography of Lee for readers who are unfamiliar with him.

2. WITNESS LEE

Lee was born in northern China in 1905 and raised in a Christian household. His mother was a third-generation Southern Baptist. Lee attended a Southern Baptist Chinese elementary school and the Presbyterian English Mission College in Chefoo.17 At the age of 19, Lee had a dynamic conversion experience after attending a gospel meeting led by female evangelist Peace Wang.18 He met in Brethren Assemblies (Benjamin Newton branch) for seven and a half years before moving to Shanghai in 1934 to work with Watchman Nee.19 Lee then served as the editor of one of Nee’s periodicals, The Christian, for six years (1934–40) while travelling to establish local churches.20 By 1949, Nee and Lee had established more than 400 congregations in 30 provinces across China.

Due to the changing political landscape, Nee implored Lee to leave China and settle in Taiwan. This proved to be a prescient proposal, as the newly formed Chinese Communist regime impris-oned Nee only three years later and subsequently arrested many other church leaders.21 From 1949 to 1962, Lee established hundreds of local churches in Taiwan, the Philippines, Malaysia, Indonesia, Singapore, Japan, and Korea.22 He settled in California in 1962, where he established a publishing house that became Living Stream Ministry,23 established over 2,300 churches (by 1996) on six continents, completed a commentary series of the 66 books of Scripture entitled Life-study of the Bible (LS), and published a series of messages outlining his theological outlook, organized along topical lines, entitled The Conclusion of the New Testament (CNT).24 He passed away in 1997 aged 91. Today, an estimated 1.5–2 million Christians meet in churches directly established by the ministry of Nee and Lee, and tens of millions of Christian believers in under-ground Chinese churches continue to be formatively shaped by their writings.25

A significant result of Lee’s six decades of ministry is a voluminous corpus. Apart from his commentaries and CNT, the recently completed The Collected Works of Witness Lee (CWWL) comprises 138 volumes containing over 78,000 pages.26 Now that the entirety of Lee’s ministry is published and digitally catalogued, a comprehensive and thorough re-examination of Lee’s understanding of the Trinity is possible.

3. THE ESSENTIAL/ECONOMIC DICHOTOMY

The distinction between the essential and economic aspects of the Trinity is a core feature of the Nicene tradition.27 The essential Trinity, otherwise known as the immanent or ontological Trinity, refers to God’s being ad intra or God in se—that is, God in Himself apart from His relationship to humans, creation, space, and time.28 The economic Trinity, on the other hand, refers to God’s being ad extra or God pro nobis—that is, God’s revelation of Himself in time and space to human beings with respect to and for the accomplishment of his eternal, salvific oikonomia.29 While both aspects are acknowledged by theologians spanning time periods, soci-olinguistic backgrounds, and theological traditions, the relationship between them is contested. Given the scope of this article, we need not trace every twist and turn in scholarship that probes the relationship between these two.30 It sufices, rather, to list three of the foremost possibilities:

(1) a historically ‘classic model’ whereby ‘the economic Trinity is the ground of cognition for the ontological Trinity, and the ontological Trinity is the ground of being for the economic Trinity’;31

(2) a ‘theology of the cross’, as advanced by Jürgen Moltmann, Eberhard Jüngel, and others which builds upon Karl Rahner’s famed axiom ‘the economic Trinity is the ontological Trinity, and vice versa’;32

(3) a purely economic model of the Trinity, perhaps best exemplified by Hendrikus Berkhof who conceives of ‘the Trinity only as an economic Trinity’.33

A note of caution: this tripartite schematic is quite broad, and fails to capture important nuances between thinkers. Moreover, one must be discerning when aiming to catalogue thinkers accord-ing to these categories. Many scholars who afirm Rahner’s rule, for example—including Rahner himself—are more closely aligned with a historically ‘classic model’ of the Trinity. Still, it is a helpful guide for our delimited purposes—that is, to discern how Lee’s essential/economic dichotomy informs his doctrine of the Trinity.

Lee contends that ‘the essential Trinity refers to the essence of the Triune God for His exist-ence; the economical Trinity refers to His plan for His move’,34 the economy of salvation for His action or activity involved in the world of creation, particularly humanity—a statement reminis-cent of the historically ‘classic model’ above. Regarding the essential Trinity, he avers that God is one essence manifested as three hypostases35 (Father, Son, and Spirit) who eternally coexist and coinhere, are immutable, and have no sense of succession among them. Ron Kangas, an able interpreter of Lee, summarizes this portrayal of the essential Trinity:

In Himself, that is, in His essence, God is uniquely one, self-existing, ever-existing, immuta-ble, triune, and characterized by life, light, love, righteousness, and holiness. … The God who is uniquely one, self-existing, ever-existing, and immutable is essentially triune; He is three-one—three yet one, one yet three. From eternity to eternity the unique God, the Triune God, is the Father, the Son, and the Spirit.36

When discussing the economic Trinity, Lee argues that the Triune God underwent scrip-turally enumerated ‘processes’ for the fulfilment of his oikonomia and insists that the outward actions of the three hypostases individually involve all of the Three of the Divine Trinity corpo-rately. While each of these commitments is expanded upon in the remainder of this article, the following two passages provide a snapshot of Lee’s understanding of the essential/economic dichotomy:

In the essential Trinity, the Father, the Son, and the Spirit coexist and coinhere at the same time and in the same way with no succession. There is no first, second, or third. However, in God’s plan, in God’s administrative arrangement, in God’s economy, the Father takes the first step, the Son takes the second step, and the Spirit takes the third step. The Father planned, the Son accom-plished, and the Spirit applies what the Son accomplished according to the Father’s plan.37

Among the three of the Divine Trinity, there is distinction but no separation. The Father is distinct from the Son, the Son is distinct from the Spirit, and the Spirit is distinct from the Son and the Father. The three of the Godhead coexist in Their coinherence, so They are distinct but not separate. In the Triune God there is no separation, only distinction.38

With this broad overview in hand, we now turn to examine the details of Lee’s portrayal of the essential Trinity.

4. THE ESSENTIAL TRINITY

In the early church, both tritheism and modalism emerged as two of the most challenging trin-itarian heresies. While modalism overemphasized God’s unity to the detriment of his trinity, tritheism overstated separation amongst the Trinity to the detriment of ontological unity. In response to both extremes, patristic trinitarian reflection incorporated the interrelated concepts of coexistence and coinherence39 (i.e. perichoresis [Gk.], circumincessio [Lt.], interpenetration) among the divine hypostases. A brief survey of the historic development of these doctrines is warranted in order to situate our ensuing analysis of Lee’s outlook.

Patristic development of the doctrines of coexistence and coinherence

Athanasius of Alexandria and the Cappadocian Fathers—Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nazianzus, and Gregory of Nyssa—were perhaps the most significant exponents of Nicene trinitarianism during the fourth century. Prior to their writings, the Trinity was often described as one God with three simultaneous modes of being. While such language can be employed within the bounds of trinitarian orthodoxy (and indeed, continues to be used by modern theo-logians such as Barth),40 greater linguistic and conceptual precision was needed to differentiate Nicene trinitarianism from modalism, Sabellianism, and Patripassianism. The Cappadocians thus proposed a new trinitarian language schema between hypostases and ousia. According to Gregory of Nyssa, hypostasis is ‘that which is spoken of distinctively’, rather than the indefinite notion of the ousia.41 The distinctiveness of the hypostases, Basil suggests, is based upon the tropos tes hyparxeos(mode of origin) of the divine hypostases: the Son is eternally begotten from the Father, the Spirit eternally proceeds from the Father, and the Father is neither begotten nor proceeds from any source.42 The eternality of these modes of origin is significant, since it entails that divine hypostases are in a state of eternal coexistence—they exist simultaneously and have always existed simultaneously; elsewise stated, there was never a point in which any of the hypostases did not exist in the past nor a point where any of them ceases to exist in the future.

While this clarification concerning the eternal coexistence of the divine hypostases served as a bulwark against modalistic portrayals of the Divine Trinity, it still allowed for tritheism. Aware of this possibility, the Cappadocians consistently incorporated the notion of eternal coinher-ence of the hypostases in their trinitarian statements.43 For example, Gregory of Nyssa states that

Everything that the Father is, is seen in the Son, and everything that the Son is, belongs to the Father. The Son in His entirety abides in the Father, and in return possesses the Father in entirety in Himself. Thus the hypostasis of the Son is, so to speak, the form and presentation by which the Father is known, and the Father’s hypostasis is recognized in the form of the Son.44

Gregory articulated an even more stringent response to tritheism. He averred that even three human beings, due to possessing the same nature, should not be spoken of as ‘three humans’, but rather as one human.45 Extending this analogy to God, he argues that the foundation of divine unity lies in the shared and unified engagement in the acts of the three hypostases.46 Based upon these convictions, the Cappadocians insisted that when speaking of God, the number three is indicative only of the quantity of ‘things,’ as opposed to possessing any explanatory power in relation toGod’s nature. While each of the divine Persons can be designated as one, they cannot be added together. This sentiment was held so strongly by them that Basil ultimately proclaimed that numbers should not even be used when referring to deity.47

The concept of perichoresis is not only present within the Cappadocian corpus; it contin-ued to be employed in trinitarian reflection in later centuries by Pseudo-Dionysius, Maximus the Confessor, and especially by John of Damascus.48 For John, the logical consequence of the homoousion (lit., same essence) of the divine hypostases afirmed at Nicaea (the Son is homoou-sios with the Father) and Constantinople (the Spirit is homoousios with the Father and the Son) was perichoresis, and thus, like the Cappadocians, he contends that the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit mutually indwell one another.49 InAn Exact Exposition of the Orthodox Faith (OF),50 John uses various and significant verbs51 to describe the relations between the hypostases, emphasiz-ing that perichoresis entails that divine Persons are both ‘with’ and ‘in’ one another.52 He insists, however, that this understanding of Divine relations results in no confusion, coalescence, or mixture of the divine Persons.53

Lee’s portrayal of the essential trinity

With the above survey serving as a backdrop, we now turn to examine statements from Lee’s corpus. In general, Lee’s trinitarianism aligns more closely with patristic outlooks than contem-porary formulations. This is unsurprising, as he cites historic Christian thinkers far more often than modern scholars. Standing in line with the Latin tradition, he uses ‘persons’ (personae) at least 296 times in his corpus when discussing the Trinity. However, in contradistinction to some contemporary scholars who view the term ‘person’ as a measure of trinitarian orthodoxy, he prefers hypostasis/hypostases54 in his trinitarian reflections due to the modern connotation of ‘persons’ referring to independent, divisible, autonomous entities. Lee discusses this pref-erence, along with other formative elements of his conception of the essential Trinity, in the following three passages:

Concerning the aspect of the Divine Trinity’s being three, another Greek word that is used is prosopa, which is equivalent to the Latin word, personae, from which the English word person is derived. However, most people today are not clear about the meanings of these terms. This is why Philip Schaff, a church historian, was in favor of using the Greek word hupostases, sup-porting substances, instead of the other terms. … The Triune God has three hupostases but only one ousia.55

In the historical study of the Divine Trinity, the word hypostasis was first used and then the word substance … In the study of the Divine Trinity the following crucial statement was made—the Triune God has three substances but only one essence … This is the essential Trinity. In essence the Father, the Son, and the Spirit are one, but in substance (person) They are three. Actually, we do not appreciate the word persons that much. Rather, we appreciate the word hypostases.56

In [John 14] verse 10 the Lord continued, ‘Do you not believe that I am in the Father and the Father is in Me?’ Over the past eighteen hundred years this truth [coinherence] has been gradually neglected. However, the theologians in the early centuries considered this matter to be quite important. They even coined the theological term coinherence, meaning that you are in me, I am in you, and we are in one another mutually. In Christianity’s theology today, many teach the doctrine of the Trinity, and some advocate the use of the term coexistence, but not many have the boldness to use the term coinherence. Nonetheless, in early Christian theology both coexistence and coinherence were used.57

Three crucial aspects of Lee’s theological outlook may be gleaned from these passages: (1) he is aware of and aligns his view with patristic trinitarian reflection; (2) he afirms the funda-mental Niceno-Constantipolitan claim, that God is ‘one ousia’ with ‘three hypostases’; and (3) he believes that the doctrines of coexistence and coinherence are necessary components that undergird a proper portrayal of the essential Trinity.

For Lee, the ecumenical creeds are useful insofar as they serve as ‘a rule of faith’ for founda-tional tenets of orthodox trinitarianism:58

By the time of the Council of Nicaea, which was held in A.D. 325 under Constantine the Great, the orthodox doctrine concerning the Triune God had been established. The ortho-dox creed formulated at the Council of Nicaea was a repudiation of both modalism, which was exemplified by Sabellius, and tritheism, which was represented by Arius. Sabellius did not believe in the simultaneous existence of the Father, the Son, and the Spirit. According to Sabellius’s view, the Father, the Son, and the Spirit were designations of three phases of the one God who manifests Himself in different ways according to circumstances. Sabellius went to the extreme of emphasizing the oneness of the Trinity to the extent of neglecting Their threeness.59

Lee contends, however, that the creeds are not suficient to articulate a comprehensive and scriptural portrayal of the Divine Trinity60 since they lack the toolset to engage with texts that do not align with terse pronouncements. Concerning this, Lee often cites: (1) statements that identify the Lord as the Spirit (1 Cor. 15:45b; 2 Cor. 3:17); (2) passages which identify the Son with and/or in the Father (Isa. 9:6; John 14:10, 20; 10:38; 17:21, 23); and(3) John’s identifica-tion of the Spirit as seven Spirits (Rev. 1:4; 3:1; 4:5; 5:6).61 Hence, Lee suggests that biblically faithful trinitarian reflection must go beyond the creeds, inclusive of incorporating robust con-ceptions of the eternal coexistence and coinherence of the divine hypostases. His writings thus, repeatedly and emphatically, reject what he deems an error of modern apologetic and evangeli-cal enterprises—an inordinate reliance upon the creeds as the sole standard of orthodoxy in lieu of both Scripture and patristic trinitarian reflection.

Lee’s doctrine of coexistence

Lee’s trinitarian reflection does not follow a standard Eastern Greek or Western Latin approach: he does not begin with the monarchy of the Father as the basis of the Godhead and move out-ward to the Son and Spirit (Eastern), nor with the divine ousia (Western). His approach, rather, is grounded in the New Testament model of monotheism—one personal God comprising three distinct Persons (hypostases).62 It is likely that Lee chose this approach due to what he believed was an implicit tritheism within broad swathes of American Christianity (particularly evangel-icalism) during the period from the 1960s to the 1990s. Moving from biblical monotheism, his theological process advances to first articulating the distinctiveness of the divine hypostases through the lens of coexistence and, thereafter, the Trinity’s ontological unity through the lens of coinherence.

The most basic understanding of eternal coexistence, per Lee, is that the three hypostases ‘exist together at the same time’.63 Lee’s doctrine, however, moves beyond this basic premiss in three directions. First, he ties the coexistence of the divine hypostases to their full divinity, indicating the real sharing or communion of the same divine ousia among the three:64

We must be clear that the Father, the Son, and the Spirit coexist simultaneously from eternity to eternity. Undoubtedly, the Father is God (1 Pet. 1:2; Eph. 1:17), the Son is God (Heb. 1:8; John 1:1; Rom. 9:5), and the Spirit is God (Acts 5:3–4).65

Second, Lee contends that each of the divine hypostases is eternal: the Father exists eternally, the Son exists eternally, and the Spirit exists eternally, which logically entails that they also exist simultaneously. In brief, when discussing the essential Trinity, Lee rejects any possibility of the divine Persons being temporary and/or successive modes of God’s activity:

He is the Triune God. The Father is eternal (Isa. 9:6), the Son is eternal (Heb. 1:12; 7:3), the Spirit is eternal (9:14), and They coexist simultaneously.66

The three of the Divine Trinity—the Father, the Son, and the Spirit—exist at the same time; and Their coexistence is from eternity to eternity, being equally without beginning and with-out ending.67

The result of these first two elements is the third component of Lee’s doctrine of coexistence: he rejects modalism as a heretical distortion of the essential Trinity.68 According to Fred Sanders, modalism refers to ‘any reduction of the three persons to mere modes, phases, or manifestations of the one God’.69 Per F. F. Bruce and Henry Chadwick, modalism is tantamount to denying that God is triune in His inner being and instead insists that God’s revelation of Godself as Father, Son, and Spirit does not correspond to the nature of the Godhead.70 Lee, concurring with Bruce and Chadwick, and aligning with the Cappadocians, believes that coexistence is a safeguard against heresy:

Modalism in the second and third centuries passed through several changes and then reached its clearest expression with Sabellius. Modalism teaches that the Father, the Son, and the Spirit are not all eternal and do not all exist at the same time but are merely three temporary mani-festations of the one God. Modalism claims that the Father ended with the Son’s coming and that the Son ceased with the Spirit’s coming. The modalists say that the three of the Godhead exist respectively in three consecutive stages. They do not believe in the coexistence and coin-herence of the Father, the Son, and the Spirit. This, of course, is a great heresy. Unlike the modalists, we believe in the eternal coexistence and coinherence of the three of the Godhead; that is, we believe that the Father, the Son, and the Spirit all exist essentially at the same time and under the same conditions. … [E]ven in Their economical works and manifestations, the three still remain essentially in Their coexistence and coinherence.71

Notably, the passage is illustrative, not exhaustive, of Lee’s rejection of modalism.72

Thus far, our analysis of statements from Lee’s corpus illuminates four key issues pertaining to his understanding of the essential Trinity: (1) at its core, Lee’s doctrine of the Trinity is pred-icated upon trinitarian axioms advanced by the Niceno-Constantinopolitan Creed; (2) Lee’s doctrine of coexistence aligns with patristic predecessors such as the Cappadocian Fathers and John of Damascus; (3) Lee aims to use coexistence as a means to demonstrate scriptural truths, such as the divinity and simultaneous eternality of the divine hypostases; and (4) Lee rejects modalism as a heretical distortion of orthodox trinitarianism. Still, one final piece of his under-standing of the essential Trinity remains to be discussed: the doctrine of coinherence.

Lee’s doctrine of coinherence

In a monograph entitled God in Three Persons, Millard J. Erickson employs a social analogy to describe the Trinity and utilizes perichoresis as a means of signifying ‘that each of the three per-sons shares the lives of the others [and] that each lives in the others’.73 Though Lee never speaks of the ‘lives’ of the divine hypostases in an equivalent ‘social’ sense, his employment of pericho-resis as it relates to sharing between the hypostases and the mutual indwelling of the hypostases aligns with Erickson’s portrayal.74 Lee avers that three related terms are crucial to apprehend when ‘studying the deep truths concerning the Trinity: the verb “coinhere,” the noun “coin-herence,” and the adjective “coinherent.”’75 Most basically, to ‘coinhere’ means ‘to exist in one another, to dwell in one another’.76 What is interesting about Lee’s perspective, however, is that the coinherence of the hypostases is not an isolated doctrine, but is inextricably linked to their eternal coexistence. Similar to what we observed with John of Damascus, Lee posits that the coinherence of the Father, Son, and Spirit is the logical result of their coexistence:77 ‘without coexisting, the three cannot inhere in one another’78 and ‘They coexist by the way of coinher-ing’.79 Also in line with John’s notion of perichoresis, Lee repeatedly contends that the coinher-ence does not, and indeed cannot, imply a merging or confusion among the divine hypostases.80 Rather, it simultaneously afirms both their distinctiveness and their perfect, essential unity, as shown in the following three sample passages:

According to the truth of the Bible, the three of the Godhead are distinct, but They are never separate. They are three because They coexist (Matt. 3:16-17; John 14:16-17; Eph. 3:14-17), and They are one because They also coinhere; that is, They mutually dwell in each other (John 10:38; 14:10; 17:21).81

In John 14:11 the Lord Jesus, the Son, said, ‘Believe Me that I am in the Father and the Father is in Me’. The Lord’s word in this verse shows the coinherence, the mutual indwelling, of the Father and the Son; moreover, it shows that although there is a distinction between the Father and the Son, there is no separation.82

This [Eph. 2:18] also indicates that the Three coexist and coinhere simultaneously, even after all the processes of incarnation, human living, crucifixion, and resurrection.83

This final passage is especially important, as it demonstrates that for Lee, the doctrines of coex-istence and coinherence are related not only to the essential Trinity, but also to the economic Trinity—an issue discussed in the second half of this article.

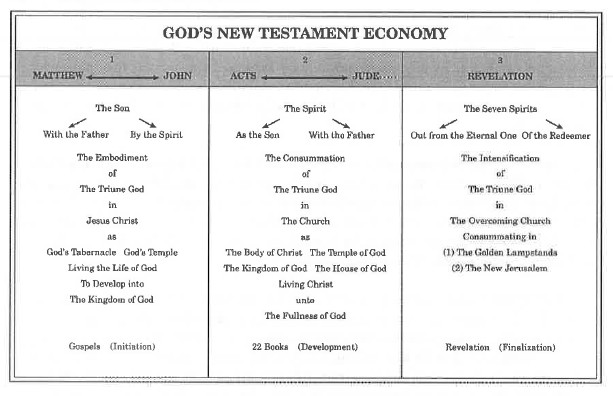

Since the medieval era, the so-called ‘shield of the Trinity’ has been utilized as a visual rep-resentation of the Trinity for laypersons to conceptualize the language of the Athanasian Creed. While useful in helping believers disavow modalism, the image was devoid of any reference to the coinherence of the divine hypostases, which allowed for the possibility that individuals might unwittingly inherit a tritheistic trinitarian outlook.84 In recent years, however, theologians such as Justin Taylor have introduced a refined shield to incorporate the idea of coinherence (Fig. 1).85

Though any visual depiction of coinherence falls short of capturing every nuance of the doc-trine, Taylor’s desire to do so is highly significant within the context of this article. Earlier, we noted that Lee’s trinitarianism was strongly criticized by various countercult ministries (most often ‘evangelical’ in orientation) during the 1970s. Lee’s notion of coinherence was one of the main targets of these criticisms. Taylor’s addition of ‘is in’ to the ‘is not’ line of this diagram demonstrates that, at least in some corners of the evangelical tradition, this historically ortho-dox perspective is garnering modern acceptance.86 We thus suggest that what this revised dia-gram represents in the evangelical imagination, along with other expressions of contemporary interest in the doctrine of perichoresis/coinherence, opens a possible avenue for reappraising Lee’s conception of the essential Trinity at the lay level.87

Much of the aforementioned controversy pertaining to Lee’s notion of coinherence was cen-tred upon a misunderstanding of his exegetical engagement with verses such as Isa. 9:6, 2 Cor. 3:17, and 1 Cor. 15:45b.88 According to J. Scott Horrell, the doctrine of coinherence allows

Fig. 1 Taylor’s Revised ‘Shield of the Trinity’ Diagram.

for the Holy Spirit to be identified in Scripture as ‘the Spirit of Christ’ and ‘the Spirit of the Father’.89 John Feinberg similarly notes that the New Testament demonstrates an ‘ontological unity’ where ‘the Father, Son, and Spirit are considered as one’:90

There are also passages that teach that the Son and the Spirit are one. In Rom 8:9–10 Paul speaks of the indwelling of the Holy Spirit, but he says that anyone who does not have the Holy Spirit does not belong to Christ. Thus, in having Christ, one also has the Holy Spirit and vice versa. All of this suggests their unity. Moreover, consider 2 Cor 3:17. As we have already seen, this verse says that the Lord is the Spirit, and the word for Lord is kyrios, the Greek for the Hebrew yhwh. Many see kyrios here as a reference to Jesus who, of course, is often called by this name. In that case, the verse asserts unity between the Son and the Spirit.91

Similarly, Lee interprets these and other verses identifying the three divine Persons through the lens of coinherence. He contends that the Son comes with the Father (John 5:43; 14:10–11, 23; 16:32; 17:21; 1 John 2:23, etc.), is one with the Father (John 10:30; 17:22), and is even referred to as the eternal Father (Isa. 9:6); the Son is also referred to as the Spirit (2 Cor. 3:17) and a life-giving Spirit (1 Cor. 15:45b).92 Per Lee,

Second Corinthians 3:17 says that the Lord is the Spirit, and 1 Corinthians 15:45 says that Christ as the last Adam became a life-giving Spirit. These verses reveal that the Son is the Spirit (John 14:16–20). Some Bible commentators have asserted that in the believers’ experience of the Triune God, Christ is identified with the Spirit; that is, Christ is one with the Spirit. The pure revelation of the Triune God according to the Scriptures recognizes the coexistence and coinherence of the three of the Godhead. The Father, the Son, and the Spirit coexist; this implies that They are distinctly three. The three of the Trinity also coinhere; this implies that They are inseparably one.93

When the Spirit comes to us, He does not leave the Father in heaven. Instead, He [the Spirit] comes with the Father and with the Son, because the Father, the Son, and the Spirit coinhere. In Romans 8 the indwelling Spirit is called the Spirit of God, the Spirit of Christ, and the Spirit of the resurrecting One.94

Lee’s controlling hermeneutic with these and other dificult texts is to exegete them accord-ing to the plain sense of the text as opposed to reinterpreting the text as if it fails to align with contemporary trinitarian thought (e.g. with Isa. 9:6, many scholars contend that the Son cannot be identified as the Father, and thus, the title must speak of the Son as Father of eternity in a metaphorical sense).95 That Lee adopts this approach is unsurprising, as his theological method prioritizes scriptural language over credal language. While Lee demonstrates adherence to the latter (i.e. his insistence upon three hypostases in one ousia), he exhibits a greater degree of com-fort than some of his contemporaries with simply repeating scriptural ‘is’ statements (the Lord is the Spirit, the Son is the eternal Father, etc.). Given the recognition of both the coexistence and coinherence of the divine hypostases, Lee contends that such verses can be articulated plainly with no threat to the coexistence of the hypostases, since it is always true that ‘they are distinctly Three’.96 Ultimately, he proclaims thats

When we say that the Son is the Father (Isa. 9:6) and the Lord is the Spirit (2 Cor. 3:17), we are simply quoting the Bible. … we believe all the verses in the Bible, which reveal the eternal coexistence and coinherence of the three of the Godhead. We condemn both modalism and tritheism as heresies.97

Regardless of whether one agrees with various particularities embedded within Lee’s notion of coinherence, two issues are noteworthy. First, Lee’s interpretation of the verses above links the doctrine of coinherence to the Son’s identification as the Father and the Son’s identification as the Spirit, which parallel to the contentions of certain prominent evangelical contemporaries, is an exegetical move with firm grounding in orthodox trinitarian thought.

Second, as Veli-Matti Kärkkäinen aptly notes, the grammar of Christian theology defines the word ‘is’ in the sentences ‘Father is God’, ‘Son is God’, or ‘Spirit is God’ as not speaking of iden-tity or inclusion, but of predication or attribution.98 Thus, for Kärkkäinen, the meaning of these statements is not to comment upon identity per se, but rather, to articulate that the Father, Son, and Spirit each possess full divinity. In a similar vein, Lee’s recitation of biblical statements such as ‘a Son is called Eternal Father’ (cf. Isa. 9:6) or ‘the Lord is the Spirit’ (2 Cor. 3:17) does not entail that the Son is the Father or the Son is the Spirit in the sense of annulling their distinct identities. Rather, these statements and others like them entail that the divine hypostases possess a supra-natural unity based upon their eternal coinherence, so that the Father shares all that he is and has with the Son, and the Son shares all that he is and has with the Spirit.

5. THE ECONOMIC TRINITY

Broadly speaking, the proper articulation of issues related to the essential Trinity is of greater import in modern analyses of what constitutes orthodox trinitarianism. Given the backdrop of why a study of Lee’s trinitarian outlook is needed—i.e. gross misrepresentations by lay apol-ogists—we began by discussing the essential Trinity. However, this assumed priority within modern apologetics is a historical anomaly. Patristic trinitarian reflection overwhelmingly began with and prioritized the economic Trinity. This should be unsurprising given that Scripture speaks far more about the Trinity as revealed in relation to creation, human beings, salvation, and the church as opposed to discussion of the inner workings of God in Godself. While there was a shift in the medieval era from prioritizing the economic Trinity to, per Fred Sanders, a ‘dangerous tendency’ of relying upon ‘speculative or metaphysical arguments’ in conceptual-izing the essential Trinity, recent scholarship is slowly returning to the impulses of the Church Fathers.99 David Coffey, for example, suggests that ‘the proper study of the Trinity is the study of the economic Trinity’.100 Because of Lee’s overriding concern to emphasize that the carrying out of the divine oikonomiais the subject of the Bible, his corpus devotes exponentially more space to discussion of the economic, as opposed to the essential, Trinity.

Before delving into Lee’s writings, it is important to note that portrayals of the economic Trinity exhibit far more differentiation in both form and content than conceptions of the essen-tial Trinity. One key reason is that all portrayals of the economic Trinity depend upon how thinkers conceive of the contours and content of the divine oikonomia. A model of the divine oikonomia which emphasizes supernatural gifts (e.g. glossolalia, healing), for example, will por-tray the missions of the economic Trinity (specifically, of the Spirit, but also the Son) in a fun-damentally different manner than a cessationist model. Various models of the atonement (e.g. penal substitution, Christus Victor, satisfaction) will similarly yield variations in how the eco-nomic Trinity is understood. Different conceptions of how predestination functions within the purview of the Father’s election also exert influence upon the economic Trinity.

As Sanders astutely notes, interpreters must ‘recognize the economy as a revelation of who God is’.101 This suggests that a proper apprehension of a specific thinker’s portrayal of the eco-nomic Trinity must begin by first understanding their conception of the divine economy. We thus begin by placing Lee’s portrayal of the economic Trinity in dialogue with his conception of the divine oikonomia. Thereafter, we discuss five additional concepts that pervade his corpus: (1) the phrase ‘processed and consummated Triune God’; (2) the concept of the ‘compound Spirit’; (3) the notion of the ‘sevenfold intensified Spirit’; (4) the ‘full ministry of Christ’; and (5) the Latin axiom opera Trinitatis ad extra indivisa sunt.

The divine oikonomia

It is hard to overemphasize the central role of the divine oikonomia in Lee’s theological outlook. At least 44 of his publications contain some iteration of ‘God’s economy’ or ‘divine economy’ in their titles, and the word ‘economy’ occurs several thousand times in his corpus. Lee provides the following working definition of oikonomia:

This Greek word is composed of two words—oikos, meaning house or household, and nomos, meaning law … In using the word oikonomia, a word that denotes a household administration, Paul was implying that God … has the intention to have a house, a household, a family. In eternity past God was alone. He was triune—the Father, the Son, and the Spirit—yet He, the one God, was alone. However, … He intended to have a household, for without a household, He cannot have an administration … This is the reason Ephesians 1:5 reveals that, before the foundation of the world, God the Father predestined us unto sonship. This predestination was with the intention of having sons. Therefore, God’s original intention was to have sons. The book of Romans tells us that, in Christ’s redemption, God has made many sinners into sons of God. These sons are the many brothers of Christ, God’s unique, only-begotten Son. From this we can see that God intends to have many sons to form His household through which He can carry out His eternal oikonomia.102

It is important to note that Lee, contrary to some modern commentators, does not conceive of God’s economic begetting of believers as sons metaphorically, nor does he restrict the notion of the believers’ divine sonship only to juridical or forensic aspects. Rather, he contends that ‘in addition to the legal status of sonship, we have the life of sonship, that is, the divine life, the life of God, which is in the Spirit of God’s Son ([Gal.] 4:6; Rom. 8:2; 1 John 5:11–12). Hence, we have the standing of sonship outwardly and the life of sonship inwardly’.103 Though Lee never uses the term ‘ontological’ in his corpus, his understanding of the believers’ newfound organic identity and ongoing organic transformation by virtue of being begotten by God as genuine sons likely warrants such description:

[A]ccording to the Scriptures, we, the believers in Christ, were all born of God to be His sons. As the sons of God, surely we are God-men. We are the same as the One of whom we were born. It would be impossible to be born of God and not be the sons of God. Since we are the sons of God, we are God-men. As sons of God and as God-men, we have the divine life … As those who are born of God, the God-men have not only the divine life but also the divine nature.104

From the above two passages, we may glean six items that are central to Lee’s understanding of the divine oikonomia:

(1) the divine oikonomia is best understood as God’s administration over His household;

(2) God’s household is comprised of Himself, His only-begotten Son (Christ), and His

many-begotten sons, the believers;

(3) the believers as the many-begotten sons of God possess divine sonship both in a judicial sense and an organic sense. That is, believers will obtain full sonship one day, but from the moment of regeneration have already obtained the life of sonship;

(4) the notion of sonship must therefore be disentangled from the modern notion of adop-tion. Sonship entails being truly begotten of God, possessing God’s life, and being indwelt by God;

(5) the trajectory of divine sonship includes both the possession of God’s life and God’s nature;

(6) being sons of God entails becoming the ‘same as the One of whom we were born’, that is, becoming God-men.

The aggregate of these points undergirds Lee’s posited goal of the divine oikonomia—the deifi-cation of believers:

Among the many truths there are three great mysteries which were discovered by the church fathers in the second century: the mystery of the Divine Trinity, the mystery of Christ’s per-son, and the mystery of man’s deification—that God became a man that man may become God in life and in nature but not in the Godhead … the Catholic Church[’s the Catechism of the Catholic Church] teaches that believers in Christ can become God … In order to be perfectly fundamental, we need to be clear concerning this great truth—the truth that God became a man that man may become God in life and in nature but not in the Godhead.105

This passage helpfully illuminates three notable aspects of Lee’s theological outlook, which in turn inform his portrayal of the economic Trinity. First, Lee draws from patristic (Irenaeus and Athanasius) and Roman Catholic (Thomas Aquinas) sources in support of his understanding of deification. Though his writings make clear that these are not sources by which he articulates his doctrine, they are proffered as support for his view. This appeal by Lee is notable given the backdrop of his critics, who often accused him of being adversarial towards Christians outside of his ministry.106

Second, Lee defines deification as becoming the same as God ‘in life and nature but not in the Godhead’.107 This terminology is important, as it disallows any notion of deification whereby believers participate in the incommunicable attributes of God, cause any change to or within the essential Trinity, or become objects of worship.

Third, Lee ranks the ‘three great mysteries’ articulated by the early church as especially cru-cial to the Christian faith: the Trinity, the person of Christ, and humankind’s deification.108 Of importance to our present investigation, all three of these truths, for Lee, are inextricably tied to the economic Trinity.

The ‘processed and consummated Triune God’

The divine oikonomia has two vantage points from which it may be discussed. The first pertains to God: that is, the acts or steps carried out by the Divine Trinity for the accomplishment of the divine economy. The second pertains to humankind or what is taking place salvifically to describe the result of these divine acts in relation to human beings participating in the divine economy. Athanasius’ famed maxim, ‘for He was made man that we might be made God’, links these two vistas.109 The latter clause, ‘that we might be made God’, is a statement from the sec-ond vantage point. The former clause, ‘for He was made man’, describes the first step—the incar-nation of the second Person of the Divine Trinity—God undertook for the accomplishment of his salvific economy. In Scripture, this act is most clearly articulated in the Gospel of John: ‘[a]nd the Word became flesh and tabernacled among us (and we beheld His glory, glory as of the only begotten from the Father), full of grace and reality’ (1:14).110 This divine act, without exception, is afirmed by all Nicene Christians.

According to Lee, this initial step, along with several successive ones, can collectively be described as a ‘process’. His use of the word ‘process’ should not be misconstrued as referring to ‘process theology’, nor should it be conflated with or read back into his portrayal of the essen-tial Trinity. It is only in relation to the divine economy, Lee contends, that the Trinity has been ‘processed’:

Change with God can only be economical; it can never be essential. Essentially, our God can-not change. From eternity to eternity He remains the same in His essence. But in His economy the Triune God has changed in the sense of being processed. First, He who was merely God became a God-man. When He was merely God, He did not have humanity. But when He changed by becoming a God-man, humanity was added to His divinity. This does not mean, however, that God was changed in His essence. On the contrary, He was changed only in His economy, in His dispensation. God has changed in His economy, but He was never changed in His essence.111

The subsequent steps Lee posits as being part of this ‘process’ form the backbone of nearly all early credal confessions: (1) Christ’s human living, (2) Christ’s crucifixion, (3) Christ’s resur-rection, and (4) Christ’s ascension. The aggregate of these acts, most basically, is what Lee aims to capture when employing the term, ‘processed Triune God’.

A sticking point for some of Lee’s critics is what he posits to be the result of this process—that is, the ‘consummated Triune God’. According to Lee, Christ, by virtue of His resurrection, was both somatically glorified andas ‘the last Adam becamea life-giving Spirit’.112 In other words, he contends that Christ simultaneously exists both in the heavens as the resurrected and ascended God-man with a glorified body and as the pneumatic Christ indwelling regenerated believers as the life-giving Spirit:

In resurrection Christ’s body was uplifted from a lower form to a higher form … that is, a body saturated with God’s glory (Phil. 3:21). Christ’s resurrected body is a glorified body of flesh and bones. At His return, our natural body, the body of our humiliation, also will be trans-figured, conformed to the body of Christ’s glory. Second Corinthians 13:5 tells us that Jesus Christ is in us, and Luke 24 reveals that Christ has a resurrected body of flesh and bones. How can Christ with His body of flesh and bones be in us? We need to realize that the resurrected Christ is the life-giving Spirit. It is as the Spirit that Christ can be in us (Rom. 8:9–11). As a man in the glory, Christ is in the heavens; as the life-giving Spirit, He is in us (vv. 10, 34; Col. 3:1; 1:27). This is a mystery. The resurrected Christ is mysterious, and He is far beyond our full comprehension.113

The Spirit was breathed into the believers by the Son in resurrection. ‘He breathed into them and said to them, Receive the Holy Spirit’ (John 20:22). The Holy Spirit here is actually the resurrected Christ Himself because this Spirit is His breath … On the day of His resurrec-tion the Lord Jesus breathed Himself into His disciples as the holy breath. The Christ who breathed Himself into the disciples is the life-giving Spirit. The resurrected Christ as the life-giving Spirit is the breath. Some theologians use the term ‘the pneumatic Christ’ to refer to the Christ who is the Spirit, the breath. After the Lord Jesus accomplished all of His pro-cesses, He became the life-giving Spirit, and the life-giving Spirit is the pneumatic Christ.114

The economic identification of Christ as the Spirit is well-attested in the Christian tradition. Patristic thinkers such as Ignatius, Tertullian, Irenaeus, Cyprian, and Athanasius all afirm the identification of the Son as the Spirit.115 Biblical scholars such as Hermann Gunkel,116 Ernst Käsemann,117 and James Dunn118 similarly recognize a scriptural basis for economically iden-tifying the Son as the Spirit. Reformed thinkers of the past century such as Charles Hodge and Lewis Smeades go as far as stating that Christ and the Holy Spirit are ‘one and the same’ and ‘inseparable’.119 And many other interpreters from centuries previous, ranging from Adolf Deissmann120 to W. H. Grifith Thomas,121 A. B. Simpson122 to Andrew Murray,123 contend that Christ is economically identified with and as the Spirit. Mehrdad Fatehi offers a particularly lucid synopsis of the Pauline identification of the Son and the Spirit:

Nevertheless, the dynamic identification between Christ and the Spirit includes, most prob-ably, also an ontic or ontological aspect, to use present day theological language and concep-tual distinctions, which goes beyond a merely functional identification. In other words, one should not speak merely of the Spirit playing the role of Christ, or of the Spirit only repre-senting Christ. Rather, there is a sense in which the risen Lord himself is actually present and active through the Spirit which is hardly imaginable without there being some ontic or onto-logical connection between the two. Thus it seems appropriate to speak also of an ontological, though dynamic, identification between the Spirit and Christ in Paul.124

Given the unfamiliar language and concepts employed by Lee, it is important to reiterate that he was not a systematic theologian, but a synthetic thinker engaging lay audiences. Though he embeds his economic Christological pneumatology within an uncommon phrase, ‘processed and consummated Triune God’,125 he always does so in implicit dialogue both with his under-standing of the essential Trinity (inclusive of his doctrines of coexistence and coinherence) and of the Latin axiom opera Trinitatis ad extra indivisa sunt (the external works of the Trinity are indi-visible). Hence, while his vocabulary may not match language commonly employed by modern (largely Western) theologians, his alignment with the above Christian interpreters pertaining to the actual doctrinal claims he embeds in the phrase ‘processed and consummated Triune God’ demonstrates that his outlook falls within the bounds of orthodox Nicene trinitarianism.

The compound Spirit

A second framework Lee employs to discuss the ‘processes’ undertaken by the economic Trinity is that of the ‘compound Spirit’. This concept, like others introduced in this article, pervades Lee’s corpus, and space constraints disallow a comprehensive presentation of nuances related to it. For our purposes, we delimit our discussion only to Lee’s posited exegetical basis for the com-pound Spirit and the theological claims he proposes based upon his scriptural engagement.126

Lee takes the word compound from Exod. 30:25: ‘And you shall make it a holy anointing oil, a fragrant ointment compounded according to the work of a compounder; it shall be a holy anointing oil’. Following Plymouth Brethren writers such as C. A. Coates and C. H. Mackintosh, Lee typologically interprets the anointing oil as referring to the Spirit.127 Lee further develops this typology, however, to argue that each of the ointment’s ingredients refers not, as Mackintosh suggests, to the Spirit’s varied graces in a general sense, but actually represents specific divine actions (or characteristics of those actions) that are ‘compounded’ into the Spirit. The following passage concisely captures several of Lee’s key claims:

In making the holy anointing oil, four spices were added to a hin of olive oil—five hundred shekels of myrrh, two hundred fifty shekels of cinnamon, two hundred fifty shekels of cala-mus, and five hundred shekels of cassia (vv. 23–24). The significances of the ingredients of this compound anointing oil are as follows: (1) flowing myrrh, a spice used in burial (John 19:39), signifies the precious death of Christ (Rom. 6:3); (2) fragrant cinnamon signifies the sweetness and effectiveness of Christ’s death (8:13); (3) fragrant calamus, from a reed that grew upward in a marsh or muddy place, signifies the precious resurrection of Christ (Eph. 2:6; Col. 3:1; 1 Pet. 1:3); (4) cassia, used in ancient times to repel insects and snakes, signifies the power of Christ’s resurrection (Phil. 3:10); and (5) the olive oil as the base of the com-pound ointment signifies the Spirit of God as the base of the Spirit.128

As noted, Lee conceives of the Spirit being ‘compounded’ with divine acts and characteristics of those acts: it is not only Christ’s death (myrrh) that has been compounded into the Spirit, but also its ‘sweetness and effectiveness’ (cinnamon); not only Christ’s resurrection (calamus), but also its ‘power’ (cassia).

Lee extends this principle of ‘compounding’ to all (economic) divine acts and all salvific ben-efits afforded by those acts to suggest that their inclusion provides the rationale for why the Divine Trinity chose to be processed and consummated. The following three passages, though lengthy, help to illuminate the central role of this outlook in Lee’s intellectual topography:

This all-inclusive Spirit is the compound of all that the Father is and has and all that the Father can do, is doing, and will do, plus the Son in His person and with His work, His accomplish-ments, His attainments, His obtainments, and all that He has gone through. The Spirit is the compound of all the divine things. It is much, much more than a power, a means, or an instru-ment. This all-inclusive Spirit is the blessing of the New Testament, and this is the blessing of the gospel, which God promised to Abraham (Gal. 3:14).129

The Spirit is the consummation of the processed Triune God given to us as the blessing of the gospel. When presenting the real blessing of the gospel, Paul does not list many items such as peace, joy, and forgiveness of sins; rather, Paul speaks only of one person—the Spirit as the consummation of the processed Triune God … The Triune God—God the Father, God the Son, and God the Spirit—has passed through processes to be consummated in the Spirit … In this compound, all-inclusive Spirit are all of Christ’s person and process, including His divinity, humanity, crucifixion for Him to accomplish redemption, resurrection for Him to give life to us, and ascension for Him to be Lord of all (Rom. 8:11; 2 Cor. 3:18). If we have the Spirit, we have everything and we are short of nothing … If we have the Spirit we have God, man, redemption, and forgiveness of sins. The Spirit is our God, our Father, our Lord, our Redeemer, our Savior, and our Shepherd; the Spirit is our life, our life supply, our righteous-ness, our sanctification, our transformation, and our redemption. The all-inclusive Spirit is the processed and consummated Triune God given to us as the blessing.130

As such a compound Spirit, Christ became the bountiful supply of the Divine Trinity for His dispensing. Philippians 1:19 uses the term the bountiful supply of the Spirit of Jesus Christ … In Greek the word for bountiful supply denotes the supplying of all the needs of a musical group by the leader of the group. Whatever the group needed, whether it was musical instru-ments, clothing, uniform, food, or medicine, was supplied by the leader. Today Christ is such a Leader. As the life-giving Spirit, who is the compound Spirit, the Spirit of Jesus Christ, He has the bountiful supply to meet all our needs … This bountiful supply comes from the source of the consummation of the processed Triune God. This consummation is the compound Spirit, and this compound Spirit is Jesus Christ.131

Based upon these statements, we see that Lee incorporates the entirety of the divine oikonomia into the ‘consummation’ of the economic Trinity. This in turn affords believers participatory access to all past divine economic acts, present divine activities, and future benefits of those acts and activities.

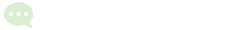

Since many moving parts have been introduced in the preceding three sections, it would be helpful to summarize this constellation of Lee’s proposals about the economic Trinity in the following schematic:

(1) the economic Trinity is inextricably related to the accomplishment of the divine oikonomia;

(2) the aggregate of divine acts undertaken by the economic Trinity is a ‘process’—a term that should not be conflated with ‘process theology’ nor with the essential Trinity;

(3) the phrase ‘processed Triune God’ refers to the divine acts of Christ’s incarnation, human living, crucifixion, resurrection, and ascension;

(4) this economic ‘process’ has an end result, a ‘consummation’: Christ has both been somat-ically glorified and has become a life-giving Spirit;

(5) Lee employs another framework to discuss the economic Trinity: the ‘compound Spirit’;

(6) though he understands these terms interchangeably (the life-giving Spirit is the com-pound Spirit and vice versa), closer analysis of the compound Spirit clarifies that for Lee, it is not only the divine economic acts that are incorporated into the Spirit. Rather, characteristics of each act are also compounded into the Spirit (e.g. not only Christ’s resurrection, but also its power);

(7) Lee contends that all the divine acts of the Father and Son, along with their salvific ben-efits, are economically compounded into the Spirit, inclusive of righteousness, sanctifi-cation, transformation, and redemption;

(8) the Spirit, for Lee, is the ultimate blessing of the New Testament, the blessing of the gospel, the blessing promised to Abraham, and the unique blessing of the Christian life.

With the above points in hand, we now turn to three final concepts which inform Lee’s under-standing of the economic Trinity: (1) the ‘sevenfold intensified Spirit’; (2) the ‘full ministry of Christ’; and (3) the Latin axiom of opera Trinitatis ad extra indivisa sunt.

The ‘sevenfold intensified Spirit’

We have thus far outlined Lee’s understanding of the processed economic Trinity, which results in a consummation—the life-giving Spirit, the compound Spirit, or simply, ‘the Spirit’. Based upon Lee’s interpretation of the book of Revelation, however, the economic Trinity undergoes one additional process: the consummated Triune God as the life-giving, compound Spirit became the seven Spirits, which Lee renders as the ‘sevenfold intensified Spirit’.

A spectrum of interpretations of the ‘seven Spirits’ in Rev. 1:4, 3:1, 4:5, and 5:6 exists among biblical specialists and theologians, ranging from the title having no relation to God (i.e. refer-encing chief angels or other semi-divine intermediaries) to being explicitly related to the Holy Spirit, whether in terms of representing pneumatic fruits, gifts, powers, etc.132 Delineating each of these possibilities lies outside the scope of this essay. It sufices for our purposes to note that Lee believes that the ‘seven Spirits’ explicitly refer to the Spirit of God. Yet, unlike the possi-bilities above, he suggests that the title refers to ‘intensifying’ of the economic Trinity for the accomplishment of the divine oikonomia:

Today the Lord is working not only as the life-giving Spirit but also as the sevenfold intensified Spirit. This Spirit may be compared to the shining of the sun spoken of in Isaiah 30:26, which says that in the millennium ‘the light of the sun will be sevenfold’.133

In the book of Revelation the Spirit is called the seven Spirits (1:4; 4:5; 5:6), the sevenfold intensified Spirit to counteract the degradation of the church. The seven Spirits in Revelation 1:4 undoubtedly are the Spirit of God because They are ranked among the Triune God. As seven is the number for completion in God’s operation, so the seven Spirits must be for God’s move on earth. In substance and existence God’s Spirit is one. In the intensified function and work of God’s operation His Spirit is sevenfold. It is like the lampstand in Zechariah 4:2. In existence it is one lampstand, but in function it is seven lamps. At the time the book of Revelation was written, the church had become degraded, and the age was dark. Therefore, the sevenfold intensified Spirit of God was needed for God’s move on earth. In Matthew 28:19 the sequence of the Triune God is the Father, the Son, and the Holy Spirit. But in Revelation 1:4 and 5 the sequence is changed. The seven Spirits are listed in the second place instead of the third. This reveals the importance of the intensified function of the sevenfold Spirit of God … The title ‘the seven Spirits’ indicates that the Spirit has been intensified sevenfold. This Spirit intensifies all the elements of the Spirit: divinity, incarnation, crucifixion, resurrection, reality, life, and grace.134

Three issues raised in these passages warrant brief discussion. First, Lee believes that the Spirit’s intensification was necessary due to the degradation of the church at the time that John wrote Revelation chapters 2 and 3. This notion of the church’s degradation, in fact, permeates much of his corpus.135 Second, Lee believes that the change in the ordering of the divine hypostases in Revelation 1 points to the increased importance of the ‘sevenfold intensified Spirit’, a point which is further examined below. Third, the result of this intensification is that all of the ele-ments that have been compounded into the Spirit are themselves intensified for the benefit of believers, inclusive of ‘divinity, incarnation, crucifixion, reality, life, and grace’. Thus, the rami-fication of Lee’s outlook is that the sevenfold intensification of the Spirit benefits the believers and was necessary (as were the other economic processes) for the accomplishment of God’s oikonomia.

The idea that the ‘seven Spirits’ in Revelation refer to the Spirit of God finds support in numerous interpreters (e.g. Albert Barnes, Robert Mounce, Henry Barclay Swete, Henry Alford, Richard Trench).136 Richard Bauckham, for instance, suggests that the number ‘seven’ refers both to the Spirit’s perfection and the Spirit’s omnipresent work among the seven churches.137 Among medieval thinkers, Richard of Saint Victor argues that the ‘sevenfold grace of the Spirit’ relates to the seven churches in a prophetic sense; that is, the sevenfold Spirit ministers to ‘the present and future state of the holy catholic church’, in which each of the seven churches fore-tells a particular condition of the universal church.138 The sixth-century Spanish patristic com-mentator Apringius of Beja argues that the title reveals that the Spirit ‘is one in name, sevenfold in power, invisible and incorporeal, and whose form is impossible to comprehend’.139 Lastly, R. Kendall Soulen suggests that the unusual ordering of the Divine Trinity in Rev. 1:4–5 mirrors later trinitarian confessions that ‘the Holy Spirit proceeds from the Father through the Son’.140 Though this brief sampling of thinkers masks nuanced differences between interpretations, they all in substance and content closely align with core issues inherent to Lee’s notion of the seven-fold intensified Spirit.

However, Lee’s proposal is not only that the seven Spirits relate to the Spirit of God, nor only that this title indicates a sevenfold intensification of the Spirit. He claims that this intensifica-tion was needed for the accomplishment of the divine economy.141 As with other elements of his trinitarian outlook (e.g. his emphasis upon the coexistence and coinherence of the divine hypostases), this proposal follows the logic of the Cappadocians, especially Gregory of Nyssa. Gregory conceives of the Spirit as the hypostasis responsible for completing the economic work of the Father and the Son in a causal sequence.142 Per Brandon Smith, conceiving of the Spirit as ‘the perfection of God’s work … comports with the idea of the perfect, complete sevenfold Spirit exercising divine power along with the Father and the Son to bring all of creation to its perfected culmination’.143 While Lee and Gregory diverge on the exact specifications of howthe sevenfold Spirit accomplishes the divine economy (or otherwise stated, how creation arrives at its perfected culmination), it is striking that they both articulate the same vision of what this accomplishment/culmination entails—the corporate deification of believers. The first passage below is from Gregory’s In illud: Tunc ipse Filius subjicitur (on 1 Cor. 15:28), the second from Lee’sCNT series:

Since by participation we are joined to the one body of Christ, we all become one body, His own. When we shall have all become perfect, then His whole body will be subject to the life-giving power [of God]. The submission of this body is called the submission of the Son Himself, since He is united [lit., ‘mingled’] with His body, which is the Church.144

God’s New Testament economy is to make the believers God-men for the constitution of the Body of Christ so that the New Jerusalem may be consummated as the eternal enlargement and expression of the processed and consummated Triune God (Gal. 3:26; 4:7, 26, 31) … For us to be deified means that we are being constituted with the processed and consummated Triune God so that we may be made God in life and in nature to be His corporate expres-sion for eternity (Rev. 21:11). The New Jerusalem is built by God’s constituting Himself into man to make man the same as God in life, nature, and constitution so that God and man may become a corporate entity.145

While much more could be said about Lee’s notion of the sevenfold intensified Spirit—a con-cept discussed in over 200 instances throughout his corpus—it sufices to note that his three proposals—(1) the seven Spirits refer to the Spirit of God, (2) the title ‘seven Spirits’ refers to an intensification of the Spirit in his operation, and (3) the sevenfold intensified Spirit is inextri-cably linked to the accomplishment of the divine oikonomia—are well-situated within orthodox Nicene trinitarianism.

The full ministry of Christ

In the final years of his ministry, Lee employed still another framework—the full ministry of Christ—to describe the process, consummation, and intensification of the economic Trinity from the vantage point of the Son’s economic activities. Since the explicit theological issues at stake in this schema are already addressed in preceding sections, a cursory overview of this model sufices for now.

According to Lee, Christ’s ‘ministry’ was not delimited to the chronology and events detailed in the four Gospels. Christ’s earthly ministry, beginning with his incarnation and concluding with his crucifixion, was only the first of three stages of his ‘full ministry’. The second stage, which Lee calls the stage of inclusion, describes Christ’s ministry as the life-giving Spirit from the book of Acts to the book of Jude. The final stage, that of intensification, refers to Christ’s ministry in the book of Revelation as the sevenfold intensified Spirit. In an introduction to a message spoken in 1996, Lee provides the following summary:

(1) The full ministry of Christ is carried out in three stages for the fulfilment of God’s eternal economy.

(2) In the first stage of incarnation to bring God into man, to express God in humanity, and to accomplish His judicial redemption.

(3) In the second stage of inclusion to be begotten as God’s firstborn Son, to become the life-giving Spirit, and to regenerate the believers for His Body.

(4) In the third stage of intensification to intensify His organic salvation, to produce over-comers, and to consummate the New Jerusalem.146

Of particular interest to our investigation, Lee links these stages to Christ’s three ‘becomings’: (1) in the stage of incarnation, the Word became flesh; (2) in the stage of inclusion, Christ became a life-giving Spirit; and (3) in the stage of intensification, the pneumatic Christ as the life-giving Spirit became the sevenfold intensified Spirit (see Fig. 2 below).147 Though it has been previously stated, it bears repeating that the Word becoming flesh, the Son becoming a life-giving Spirit, and the life-giving Spirit becoming the sevenfold intensified Spirit are all economic processes for Lee. They do not impact nor endanger the immutability of the essential Trinity. It is impor-tant to note, however, that while changes occurring in relation to the divine oikonomia stay in the oikonomia, the reverse is not always true: core aspects in the essential Trinity continue to be necessary elements for discussing the economical Trinity. Pertinent to our present concerns (as we shall now see), Lee posits that the doctrines of eternal coexistence and coinherence—which as we saw earlier, together function as twin pillars in his portrayal of the essential Trinity—are constitutive elements of the economic Trinity.

The Latin axiom opera Trinitatis ad extra indivisa sunt

The Latin axiom opera Trinitatis ad extra indivisa suntrefers to the notion that ‘economic divine agency belongs to the Trinity as a whole, with particular actions such as creation, redemption, incarnation, etc., being appropriated to one of the divine persons’.148 In other words, while spe-cific economic acts are appropriated to individual hypostases (e.g. it is the Son that was cruci-fied, not the Father),149 all acts undertaken by the economic Trinity are externally collective in terms of divine agency, will, presence, and involvement. While this understanding of the economic Trinity is at odds with the increasingly popular notion of social trinitarianism,150 it is well-established in orthodox Nicene trinitarianism. Even the Cappadocians,151 despite their common association with social trinitarianism, were unequivocal in their afirmation of the uni-fied action of the Divine hypostases.152

Beyond Gregory and Basil, consensus pertaining to the indivisibility of trinitarian economic acts is afirmed by thinkers ranging from Augustine to Corenulius Van Til, John Owen to T. F. Torrance, and many others.153 In light of this expansive witness within the Christian tradition, Kyle Claunch notes the following summary:

Understood as a consequence of this account of divine unity, the doctrine of the insepa-rable operations of the Trinity ad extra contends that all of the works of the Triune God with respect to the creation are works of all three persons of the Godhead. This doctrine, often expressed by the Latin axiom, opera trinitatis ad extra sunt indivisa has been a staple of orthodox Trinitarian theology for centuries. Statements and defense of the doctrine can be found among the Church fathers of the East (e.g. Athanasius and Gregory of Nyssa) and the West (e.g. Hilary of Poitiers and Augustine) as they engaged in anti-Arian polemical dis-course. The doctrine is later expressed and defended by the medieval giant Thomas Aquinas and is fully embraced by the seventeenth-century Reformed Orthodox in their polemical engagement with the Socinians. The nineteenth-century heirs and defenders of Reformed Orthodoxy (e.g. Herman Bavinck and Charles Hodge) also held to this doctrine without wavering.154

Now a question remains: how does the principle opera Trinitatis ad extra indivisa sunt within the Christian tradition compare to Lee’s conception of the unified acts of the divine hypostases in God’s oikonomia? To answer this, we must pay attention to three exact phrases Lee utilizes in his corpus: (1) the Father acts in the Son and with the Spirit, (2) the Son acts with the Father and by the Spirit, and (3) the Spirit acts as the Son and with the Father. Each of them is articulated in the summary of his economic trinitarianism below:

According to the economical aspect of the Trinity, the Father planned, the Son accom-plished, and the Spirit applies to us what the Son has accomplished according to the Father’s plan. The Father accomplished the first step of His plan, His economy, by working to choose and predestinate us, but He did in Christ the Son and with the Spirit (Eph. 1:3–5). After this plan was made, the Son came to accomplish this plan, but He did this with the Father (John 8:29; 16:32) and by the Spirit (Luke 1:35; Matt. 1:18, 20; 12:28). After the Son accomplished all that the Father had planned, the Spirit comes in the third step to apply all that the Son accomplished, but He does this as the Son and with the Father (John 14:26; 15:26; 1 Cor. 15:45b; 2 Cor. 3:17). In this way, while the divine economy of the Divine Trinity is being carried out, the divine existence of the Divine Trinity, His eternal coexist-ence and coinherence, remains intact and is not jeopardized. In the divine economy the three work and are manifested respectively in three consecutive stages. Yet even in Their economical works and manifestations, the three still remain essentially in Their coexistence and coinherence.155

In Life-study of Mark, Lee includes a chart that captures his understanding of the divine oikono-mia, the full ministry of Christ, and the indivisibility of the external works of the Trinity (Fig. 2).

The above statement from Lee alongside this chart brings our analysis of his trinitarian out-look full circle, as both illumine that Lee employs both coexistence and eternal coinherence to simultaneously argue for differentiated, but inseparable economic acts of the divine hypostases: the Father chooses and predestinates in the Son and with the Spirit, the Son accomplishes acts with the Father and by the Spirit, and the Spirit applies Christ’s accomplishments as the Son and with the Father. Analysis of this final element of Lee’s portrayal of the economic Trinity demon-strates further coherence between his theological outlook and orthodox Nicene trinitarianism; and, in some ways, perhaps even greater alignment to patristic trinitarian reflection than some popularized trinitarian outlooks in modern Christian discourse.

Fig. 2 Lee’s Portrayal of God’s New Testament Economy.156

6. SYNTHESIS OF LEE’S TRINITARIAN COMMITMENTS